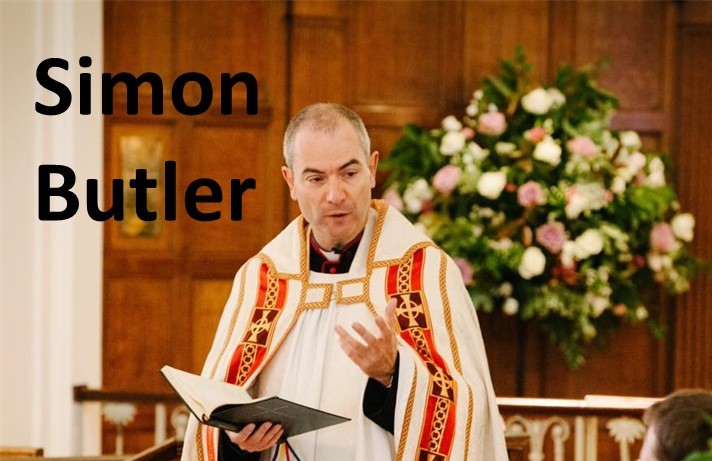

by the Revd Canon Simon Butler, Prolocutor of the Province of Canterbury and Vicar of St Mary’s, Battersea

Years ago I was invited by my then bishop to attend a day conference on Deliverance Ministry, about which he was a prominent advocate. At his invitation, a woman he said was an ‘anointed prophet’ was asked to prophesy to the group. What followed disturbed me deeply: intimate things were said as if by God to those present which seemed to be accepted as entirely authentic, without being weighed, and in a way that seemed closer to the fortune-teller’s booth than any biblical understanding of prophecy. There was a culture of ‘group-think’ present that assumed that the title of ‘prophet’, the track-record from her parish and the bishop’s imprimatur confirmed the truth of her words. It made me very angry.

When we reviewed the session I raised my concerns with the bishop about what had just happened. The bishop listened politely and, for the rest of the conference, I was firmly and clearly side-lined: I had a problem with my anger that “the Lord wanted to deal with.” From that moment on the bishop never invited me to join any future training: critical voices were not encouraged.

At the time of the incident above I was serving in a church associated with Charismatic Renewal, although our congregation was predominantly working-class. The typical church member had a life which was complex, messy and far from straight-forward. My boss and I often contrasted the life-situations and preoccupations of middle-class Charismatics with the needs and priorities of our own folk. Pentecostal form of Christianity are often found most powerfully in communities of the marginalised. I still like to think of myself as a sort of charismatic, open to the inspiration of the Spirit and ministering alert to when the Spirit speaks: at our own church we offer a sensitive ministry of healing and wholeness.

But among some Charismatics at the moment there is a concern that safeguarding is being used as a Trojan Horse to attack their freedom to believe and practise their form of Christian faith, including the use of charismatic gifts. This is because a number of people have started to speak about their own experience of poor treatment, bullying and coercion associated with churches where the added dimension is the unchallenged way in which the Holy Spirit is presumed to speak through certain ‘anointed’ leaders, lay and ordained. As I experienced in a modest way those years ago, when someone asks questions or critiques bad practice or simply doesn’t go along with ‘the leadership’, subtle or overt changes in relationship dynamics can occur. This sort of spiritual abuse isn’t inherent in Charismatic forms of Christianity, and it certainly isn’t restricted to it.

But, where the problem lies for Charismatics is the appeal to the Holy Spirit – if you don’t go along with what the Spirit is saying, you are quenching the Spirit, or (in a tradition with an occasionally baroque demonology) even possessed by a ‘spirit of rebellion’ which needs exorcising. Such appeals can amount to little more than a power grab by insecure or inexperienced leaders who, when faced with criticism, cannot face it or adapt. At a time when the Archbishops’ Council is funding significant work aimed at planting congregations with younger leaders, many of them emerging from the larger Charismatic churches, attracting younger disciples, it is important that firm, mature oversight is given, perhaps at a much closer level than the typical laissez-faire style of episcopal leadership.

With the publication of Living in Love and Faith, it is often LGBTI+ voices that are articulating these concerns, and especially the misuse of charismatic gifts. This naturally presents particular challenges to those leading churches where the theological wind blows conservative on matters of sexuality. I offer this to my Charismatic friends: please listen to these voices. If you hear such stories from LGBTI+ church members, please don’t write them off as revisionism. Hearing such stories is a pathway to growth: they allow a mirror to be held up to a less-appealing part of your culture. This could be an opportunity: although it is painful to live through, the stories of poor treatment, marginalisation and occasionally abuse are important for you to hear.

Perhaps it is the LGBTI+ voices that are the prophets among you?